Summary

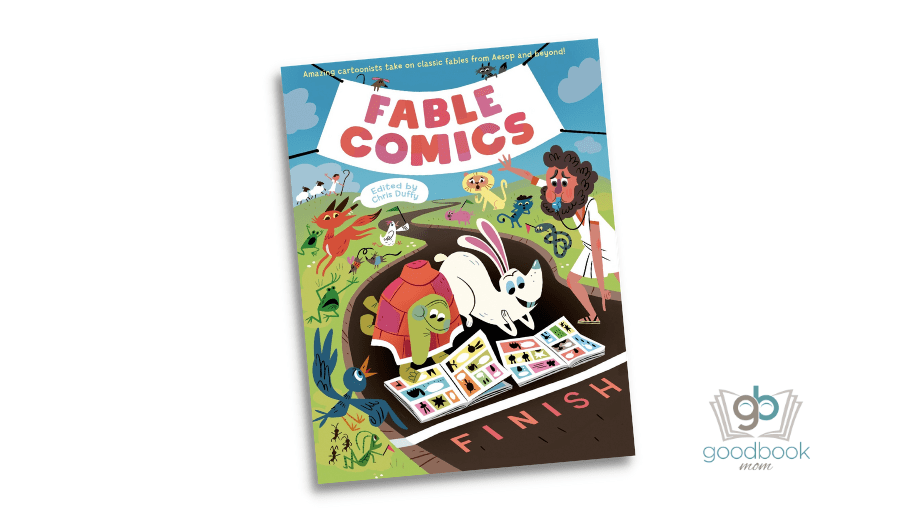

Editor Chris Duffy, known also for his New York Times bestselling collection Fairy Tale Comics as well as Nursery Rhyme Comics, has curated an entertaining and visually fascinating collection of stories. Duffy is also a talented creator in his own right, having written comics for DC and Marvel. He has an eye for creative talent, as he has pulled together here a diverse collection of illustrators and artists to bring ancient fables to a new generation.

Fable Comics has a simple premise: assemble a collection of fables from around the world and commission a variety of comic illustrators to re-interpret each story in their own distinctive artistic style. Most of the fables in the book are from Aesop’s Fables; however, the collection includes other fables from around the world including Angola, India, Russia, and even American short story writer/satirist Ambrose Bierce.

In his editor’s note, Duffy explains that each contributing cartoonist exercised creative liberty in re-telling the stories or even embellishing the stories; they simply had to maintain a central lesson. (Duffy refers to fables in his editor’s note as “bossy stories.”)

Readers with some familiarity with Aesop’s Fables may notice that while some illustrators were faithful to the original fables, others seem to have had some fun with re-interpreting the stories, and in some cases, presenting an entirely different perspective. For example, in “The Hare and the Tortoise”, the reader will likely find him or herself unexpectedly rooting for the hare. And in “The Grasshopper and the Ants”, the illustrator chose to rewrite the ending so that the ants would come to the grasshopper’s rescue.

Reading Level: 9+

Mom Thoughts

Many kids won’t perk up at the idea of reading stories from many centuries ago. So how can we prove to them that the best stories can transcend culture and time?

In the quest to make old stories feel new again, Fable Comics offers Exhibit A.

In the four Gospels, Jesus used the narrative style of the parable to explain challenging concepts like the kingdom of God. Similar to how Jesus instructed his disciples through storytelling and parables, fables provide children with an approachable doorway into learning moral lessons about human nature and about the world around them.

It is worth clarifying that Fable Comics by no means presents a biblical worldview, nor does it point children to the gospel of Jesus Christ. But what it does accomplish is two-fold. First, it breathes new life into centuries-old classic stories through the power of inventive and playful illustrations. These very old fables felt fresh in the hands of these 26 gifted artists.

Second, Fable Comics reintroduces the reader to literature that, despite the fact that it is secular in nature and not written from a Christian perspective, still emphasizes the importance of virtue. What a refreshing reminder of the common grace of great human storytelling that also seeks to cultivate moral integrity.

One of the standout features of Fable Comics is the distinctive artistic style of each illustrator, on full display as the reader moves from one comic to the next. For example, “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” and “Lion + Mouse” hearken back to the retro comics you’d read in the newspaper, even down to the use of primary colors. “Fox and Crow”, on the other hand, uses highly stylized illustrations, a moody color palette, and intense contrast between light and shadow. Some artists used abstract images to illustrate the story (and give the story impact), like “The Old Man and Death.” And others, like “The Grasshopper and the Ants” and “The Great Weasel War” utilized significant detail and artistic complexity. It was fascinating to compare and contrast the illustrators’ widely divergent choices for each fable. The artistic, highly visual kids in your life will love it.

Despite relatively simple prose that a lower elementary student could understand, many of the stories incorporate subtext and nuance, which would be better suited for a more advanced reader. (There are notable exceptions to the simple prose, as in “Man and Wart”, which has some very difficult vocabulary.) In addition, some of the illustrators made the creative decision to utilize text sparingly in their stories, requiring the reader to do a bit more heavy lifting with regard to interpreting the illustrations, facial expressions, etc. as in “The Dog and His Reflection”.

Language:

Coarse Talk: use of “@#&%” to convey cursing in “The Old Man and Death”; “what the heck?” and “gosh darn” in “The Hare and the Pig”

Tortoise is angry and vengeful in “The Hare and the Tortoise”. He says things like, “Shut yer carrot hole, you windbag!” and “I’m so sick of your durk duckety yapping” and “What the clockety clock” and “In your face, you frickety fracking rabbit!”

Name-calling: Hermes tells a human, “You can’t lie to me! I’m the god of liars, you dork!” Hermes employs amusing modern day slang, like “bummer”

Questionable Behaviors:

Reference to “ale” in “The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse”, which seems to act as a symbol of abundance

Artist George O’Connor illustrates four of the fables in Fable Comics, the only artist to be represented multiple times in the book. He depicts the Greek god Hermes in each of his fables, as well as Zeus in “The Frogs Who Desired a King”

Cartoon depiction of a demon who tries (and fails) to outsmart a thief in “The Demon, the Thief, and the Hermit”. Instead, they mutually self-destruct. In the same story, there is a “magical” cow with a never-ending milk supply.

Confusing manner of speaking for the characters in “Lion + Mouse” which made it difficult to follow. Strange romantic undertones at the end. My least favorite.

Violence:

Cartoonish violence involving a jetpack crash in “The Fox and the Grapes” as well as punches and wrestling moves in “The Dolphins, the Whales, and the Sprat”

Implied (not shown) attack of a snake upon a group of frogs in “The Frogs Who Desired a King.”

In “The Thief and the Watchdog”, the illustrator depicts the thief as being chased by the watchdog into a river, where he plunges to his death over a waterfall. He subsequently descends into the water, past likely a depiction of Poseidon, all the way to the underworld, where he has died (he is now drawn as a spirit). But Cerberus, the three-headed “Hound of Hades”, waits there for him.

Sexual Content:

The titular milkmaid in “The Milkmaid and Her Pail” has an unhealthy fixation on attracting boys’ attention.

Other Things to Know:

Some illustrators chose to include the explicit moral at the end of their story; others do not present the moral at all and assume the reader will discern the moral for him or herself.

This review was written by Good Book Mom contributor, Nancy. To learn more about Nancy, click HERE.

This post may contain affiliate links. Please read our disclaimer for more info.

Buy This Book

At A Glance

| Number of Pages | Number of Fables |

|---|---|

| 128 | 28 |